Wokeness as a Higher Consciousness

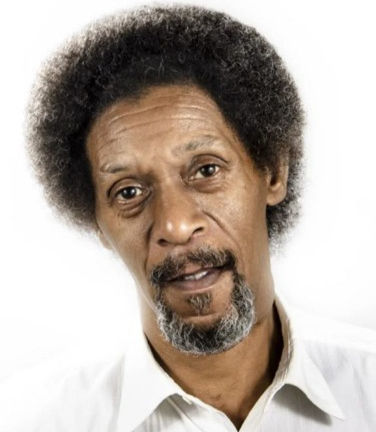

- George Payne

- Nov 18, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 18, 2024

One of the most frequent critiques leveled against the Democratic Party is that they have become “too woke.” Critics claim that the focus on progressive social issues, identity politics, and "political correctness" has overshadowed the party's ability to connect with working-class Americans and appeal to a broader electorate. Some have gone so far as to say that "wokism" got Trump re-elected.

Wokeness, as it is commonly understood in today's political discourse, is often framed as a divisive, even dangerous, ideology that undermines traditional values. But in the way I understand it, wokeness is not a political trend or a superficial label. It’s a state of higher consciousness—one that encourages us to be vigilant, informed, and empathetic. To be “woke” is to be awake to the complex, often painful realities of history, society, and identity, and to recognize that true progress means acknowledging these truths rather than burying them. Far from a threat, wokeness is an invitation to expand our perspectives and cultivate greater equity and understanding. In this sense, being "woke" isn’t about alienating voters—it’s about engaging with the issues that shape the lives of many marginalized communities and pushing for a more inclusive, just society.

When people claim that "wokism" is a problem, what they are really saying is that equality is a problem. To be woke is essentially to believe that all humans are created equal. This is not a radical concept; it’s a fundamental belief enshrined in our founding documents. Thomas Jefferson himself was echoing a woke sentiment when he wrote about the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. He wasn’t just describing a political ideology—he was articulating a belief in human dignity and equality that transcends race, gender, and class.

This kind of consciousness has roots that run deep in American history. Many of the nation’s historical figures would likely be considered “woke” today, as they were unafraid to challenge prevailing prejudices and stereotypes. Take, for example, Benjamin Franklin and William Penn, two individuals who resisted the racist narratives of their time toward Native Americans.

Benjamin Franklin did more than just question colonial prejudices—he openly admired aspects of Native American society. In his writings, he often praised the Iroquois Confederacy’s governance and systems of cooperation, which he saw as potential models for the colonies. Franklin recognized that Indigenous societies were often more democratic and equitable than their European counterparts. His willingness to learn from and respect Indigenous cultures reflects a spirit of wokeness that valued diversity of thought and questioned dominant assumptions.

William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania, also challenged colonial norms through his respectful approach to Native American-relations. A devout Quaker, Penn held to values of equality and peace, beliefs that informed his interactions with Native tribes. Rather than imposing force, Penn pursued treaties and agreements, most notably the Treaty of Shackamaxon with the Lenape tribe, which promoted coexistence. For his era, this was a radical stance, one that held respect for other cultures over the colonial impulse to dominate. Both Franklin and Penn exemplified the power of a conscious, respectful perspective that refuses to accept oppression or dehumanization. Simply put, wokeness is not a threat to American values but an expression of them.

To be “woke” is also to recognize history honestly, acknowledging that injustices like slavery, segregation, and systemic exclusion are not distant relics but active legacies shaping today’s society. Historical evidence and research affirm that the legacy of slavery in America contributes to generational trauma and persistent inequalities today. Studies in psychology and sociology demonstrate how the experiences of past generations shape present realities, creating economic and educational divides that cannot be ignored. Dismissing this awareness as “divisive” does not erase the impacts of these injustices; it only allows them to persist. Wokeness calls us to engage with these uncomfortable truths and to recognize how deeply they echo within our institutions.

Wokeness today, like in the days of Franklin and Penn, challenges us to embrace a consciousness that sees diversity as a strength, not a threat. It invites us to step out of the fear that expanding the table means less food for everyone. Instead, it reminds us that inclusive societies flourish precisely because they are more just and equitable. Wokeness encourages us to build a longer table, not a higher fence—a more just society rather than a fractured one.

When I think of wokeness, I also think of individuals who have been ahead of their time, challenging systemic inequalities in ways that are still relevant today. John Stuart Mill, a 19th-century philosopher and political economist, was one of the earliest and most influential male advocates for women's rights. In his groundbreaking work, The Subjection of Women (1869), Mill made a compelling case for women's suffrage and equality, arguing that gender equality was not only morally right but essential for a just society. His ideas laid the groundwork for future generations to continue the fight for equality.

Similarly, Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist and former enslaved person, was not only a passionate advocate for the abolition of slavery but also for women's rights. Douglass attended the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, where he spoke out in favor of women's suffrage, recognizing the intersection of racial and gender oppression. His willingness to challenge both slavery and the gender norms of his time reflects a deep, woke consciousness—one that calls for justice and equality for all people, regardless of race or gender.

Another powerful example of historical wokeness in action is Captain Robert Gould Shaw. Shaw, a white officer during the Civil War, led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first all-Black regiments in the Union Army. At a time when many Americans viewed Black soldiers as inferior or unsuitable for combat, Shaw took a stand against this prejudice. He not only fought alongside his troops but advocated fiercely for their rights and equal treatment. Shaw’s leadership was grounded in his belief that Black men were equally capable of bravery, discipline, and sacrifice. Despite facing systemic discrimination, the regiment demonstrated extraordinary courage, most notably in the assault on Fort Wagner, where Shaw and many of his men lost their lives. This battle symbolized the regiment’s determination and the larger fight for freedom and equality. Shaw’s commitment to racial justice and his willingness to challenge the norms of his time express an awareness of inequality, a refusal to accept injustice, and a commitment to equity and respect.

As I reflect on wokeness as a higher consciousness, I cannot ignore those who have always carried the light of this awareness. The Indigenous peoples of this land—the original stewards—are among the first to awaken to the true essence of justice and equality. The wisdom of Native ancestors, who held deep connections to the Earth, to one another, and to the sacredness of life itself, has always embodied a spirit of wokeness. They are the true trailblazers, whose sacred knowledge has guided us long before any labels or political movements emerged.

I also want to acknowledge the women who came before all of us—the ones who gave birth not just to our bodies but to our very dreams. The resilience, strength, and wisdom of women throughout history, especially women of color, have long been a force of transformation. They are the backbone of every movement for justice, every fight for equality, and every victory for freedom. These women knew before anyone else that their voices had power and that their purpose was never defined by society's constraints.

And let us not forget those who survived, despite the horrors of slavery. Those who never believed that they were mere slaves—those who saw that they were kings and queens in waiting, who knew that their rightful place in history would one day come. Their legacy is the foundation upon which the fight for justice continues to stand.

~ George Cassidy Payne is a writer and educator. He lives in Irondequoit, NY.

References

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Anti-Slavery Office, 1845.

Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. 1791, Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/148.

Jefferson, Thomas. The Declaration of Independence. 1776, National Archives, www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/declaratio.html.

Mill, John Stuart. The Subjection of Women. 1869, Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/27077.

Penn, William. The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience Discussed. 1670, Early Quaker Writings, www.earlyquakerwritings.com.

Shaw, Robert Gould. 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/.

Your opinion, in my opinion, is profound. While I will copy and paste and send it, it deserves to be carved in stone, read to children, and become familiar reading to the unwoke far right .

Jefferson is remarkable for being both awake and asleep.

Who else could we add to this list?